Recovery from the next recession will depend on state and local governments

After 2007, municipal austerity offset federal stimulus. In the next recession, it may have to be the other way round.

As recession fears grow, it’s natural to look back to the experience of past downturns to think about how we might better prepare for the next one. Here is one lesson: We’re less likely to see a deep and persistent downturn if we can sustain state and local government spending.

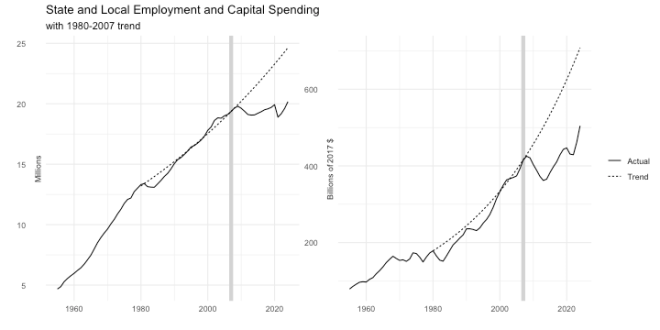

An underappreciated macroeconomic development of the past decade was the sustained turn to austerity at the state and local level. Between 2007 and 2013, state and local employment fell by 700,000 — a decline without precedent in US history. If public employment per capita were the same today as in 2005, there would be more than 2 million additional people working for state and local governments.

Some may see this as a good thing — fewer public employees means less government waste.

But in the American federal system, it is state and local governments that provide the public services that people and businesses rely on. In our daily lives, we depend on teachers, firemen, sanitation workers, librarians and road crews employed by our state, county or city. The only federal employee we are likely to encounter is the person delivering the mail.

And from an economic standpoint, spending is spending, whether useful or wasteful. There are still debates over whether the 2007 stimulus was big enough. But what’s sometimes forgotten is that increased federal spending was accompanied by deep spending cuts at the state and local level. As a share of potential GDP, state and local spending fell by a full point between 2007 and 2013, and has remained at this lower level ever since. As people like Dean Baker and Rivka Deutsch warned at the time, these cutbacks canceled out much of the federal stimulus.

Some might argue that these spending cuts, while unfortunate, were unavoidable given state balanced-budget requirements. It is certainly true that state governments have less fiscal room for maneuver than the federal government does, and local governments have still less. But balanced-budget rules don’t mean that these governments cannot borrow at all — if it did, there wouldn’t be a $3 trillion municipal-debt market.

Balanced budgets mean many things. In some states, balanced budgets are written into the state constitution, but in others, they are simply statutes that can be waived by a vote of the legislature. In some places, revenues and expenditure must actually balance at the end of the year, while in others, the adopted budget must balance but the state may end the year with a deficit if revenues end up falling short. Most important, balanced budget rules normally apply only to the operating budget; they don’t restrict borrowing for investment spending.

Yet it was state and local investment that fell most steeply following the Great Recession. Adjusted for inflation, state and local capital expenditure fell by 15 percent between 2007 and 2013, by far the steepest drop on record. In real terms, investment spending at the state and local level was no higher in 2022 than it was 15 years earlier.

Not surprisingly, this fall in state capital spending was accompanied by a fall in state and local borrowing. Over the decade of the 2010s, nominal state and local debt was flat. In other words, net borrowing by state and local governments was essentially zero — the first sustained period in modern US history where that was true. This persistent loss of demand may have done as much as the disruptions to the financial system to hold back recovery after the 2007-2009 recession.

In 20078, there was a fiscal response on the federal level, even if it turned out to be too small. In the current climate, that seems unlikely. So whether the next recession is followed by a quick recovery or turns into a sustained period of weak growth, will depend even more on how well state and local spending holds up.

It’s not hard to imagine governments feeling compelled to curbing spending in a downturn. Many are already stretched thin even in these comparatively flush times. Maryland and Los Angeles, for example, both recently saw their credit ratings downgraded. Washington DC, whose tax base is suffering from federal layoffs, already faces rising borrowing costs.

Even where the local economy holds up better, governments may feel it is prudent to cut back on investment — a classic example of a choice that may look individually rational but, when taken across the board, is collectively self-defeating, as spending cuts in one place result in lost income elsewhere.

Nor is state fiscal capacity only a concern in a downturn. It will take years for to return many federal services to their pre-DOGE levels, assuming future administrations even wish to do so. But demand for these services has not gone away. So states — especially larger ones — may find themselves forced to assume responsibility for things like food safety or weather data, for which they previously depended on Washington. States and localities may also find themselves paying more in areas where they already had primary responsibility, like education and transportation. All this will call for bigger budgets and, at least in some cases, more debt, not just in a recession but perhaps indefinitely.

What can be done to help states find the financial space to maintain spending in a downturn, or to increase it to compensate for federal cutbacks?

The most basic, but also most difficult, requirement is a change in outlook among state and local budget officials. The idea that government should spend more in a recession is a hard enough sell at the federal level; it’s not something state (let alone local) officials think about at all. The natural instinct of state budget makers to federal cutbacks will be to cut their own spending as well; it will not be easy to convince them that they should, in effect, steer into the skid by spending more.

But circumstances can force policymakers out of their comfort zones. The problems of providing public goods and stabilizing the macroeconomy will not go away just because the federal government steps back from solving them. Even if it’s impossible for other levels of government to fully replace the federal government, small steps in that direction are still worth taking. We can’t expect states and localities — even California or New York City — to recreate NASA or NIH. But it is certainly possible for state and local governments to do more with their budgets than they currently do.

In a number of states, even capital spending is financed out of current revenues rather than with debt. Unsurprisingly, public investment in these states appears to be more pro-cyclical than elsewhere. A taboo against borrowing even for capital projects means, in effect, letting fiscal space go to waste. This will be especially costly in a downturn if a federal stimulus is not forthcoming.

Almost all states have constitutional or statutory ceilings on debt and debt service. In practice, these limits are more important than balanced-budget rules, since they apply to borrowing for capital spending as well as operations. These are worth revisiting. There is nothing wrong with these in principle. But in some cases, they may be excessively restrictive, limiting the issue of new debt even in cases where the risks are minimal and the social value is great.

Of particular concern are limits that are based only on the most recent year of tax revenue or state income, rather than an average of the past several years. These rules can impart a pro-cyclical bias to capital spending, reducing it during a recession even though that is when it is most macroeconomically valuable, and when borrowing (and perhaps other) costs are lower. It’s a perverse form of fiscal guiderail that encourages states to borrow when interest rates are high, and discourages it when rates are low.

Another important limit on state fiscal space is credit ratings. State and local budget officials are deeply protective of their credit ratings; fear of a downgrade can discourage new borrowing even when there is no legal obstacle and when the capital projects it would finance are sorely needed. These concerns are certainly understandable, if perhaps sometimes exaggerated. The problem is that rating agencies may not be the best judges of government credit risk.

In the wake of the financial crisis of 2007-2009, there was a brief period of intensified scrutiny of rating agencies’ practices. The obvious problem was the AAA ratings given to mortgage-backed securities that, in retrospect, were anything but risk-free. But on the other side, rating agencies were giving systematically lower ratings to municipal borrowers than to corporate borrowers with the same chance of default. A review by Moody’s at the time suggested that the historical default rate on A-rated municipal bonds was comparable to that on AAA-rated corporate debt.

This problem has receded from view, but it was never really addressed. More recent studies have confirmed that, after adjusting for their different tax treatment, municipal borrowers pay substantially higher interest rates than corporate borrowers with similar default risk — a difference that might be explained, at least in part, by their different treatment by rating agencies.

More broadly, credit ratings are a problematic service for for-profit businesses to provide in the first place. By their nature, they need to be freely available to anyone who might buy the rated debt. Meanwhile the debt issuer, who pays for them, has opposing interests to those of the lenders who will use them. Credit ratings are public goods; there’s a clear case for them to be provided by a public rating agency, as someeconomists have proposed. If bond ratings were a public service, based on consistent, transparent principles, that might relieve some of the anxiety that deters state and local governments from making full use of their fiscal capacity.

A more radical idea would be a public option not just for credit rating, but for lending. A few years ago, there was a wave of interest in the ideaof a national investment authority. These proposals did not really make sense in the form they were originally put forward; given that the federal government already enjoys the lowest interest rate of any borrower in the economy, there is no use in creating a new entity to issue debt on its behalf. But there is a better case for a new public entity to lend to state and local governments, which face more serious constraints on their financing.

Unfortunately, the same federal retrenchment that calls for a larger role for state governments, also means proposals like a public rating agency or a national investment authority are unlikely to get off the ground for the foreseeable future.

The one place where capacity does still exist at the federal level is the Federal Reserve. Indeed, thanks to the Supreme Court’s ruling in Trump v. Wilcox, the Fed’s stature has been elevated; it is now, apparently, the only independent agency constitutionally permitted at a federal level.

Many people (including me) have long called for the Fed to support the market for municipal debt, in the same way that it supports other financial markets. For years, there was debate about whether this was something the Fed had the legal authority to do. But during the pandemic, the Fed made it clear that it did, by creating the Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF), which promised up to $500 billion in loans to state and local governments.

In the event, only a handful of municipal borrowers made use of the MLF. But as thoughtful observers of the program pointed out, this greatly understates its impact. The existence of a Fed backstop meant that muncicpal borrowers were less risky than they would otherwise have been, which allowed them to access private credit on more variable terms. A study from the Dallas Fed found that, despite its limited makeup, the existence of the MLF led to interest rates on municipal bonds as much s five points lower than they otherwise would have been.

Like many pandemic measures, the MLF was quickly wound down. But there’s a strong case that something similar should become part of the Fed’s permanent repertoire.This wouldn’t have to be an open ended commitment to lend to local governments; it might, for instance, be offered only in response to natural disasters — or recessions.

Supporting state and local borrowing is presumably not a role that the Fed wants. Stabilizing demand is definitely not a role that state governments want. In a more rational political system, these responsibilities would land elsewhere. But in the real world, problems must be solved by those who are in a position to solve them. If the federal government is stepping down, someone else is going to have to step up.

This is an expanded version of a piece that first appeared in Barron’s.

Granting more fiscal room to manoever and thus allowing state and local governments greater flexibility in independant fiscal policies, especially debt ceilings and credit policies might be a step in the right direction. Greater fiscal independance for regional governments has proved well in China. But it is a different fiscal policy with quite strict capital controls in place, although these could not prevent speculation in the real estate sector. Capital controls on the other hand are an instrument America will never entertain again - since modern day financial markets definitely want to avoid another ‘New Deal’ era.

Ellen Brown also talks a lot about state-banking models which would basically be targeting non-speculative fiscal policies of local governments and turn out beneficial when it comes to anti-cyclical spending.

without even reading this I will ask, has it never not?